The hideous pollution case I stumbled on illustrates our failure to see the harm caused by animal farming.

The hideous pollution case I stumbled on illustrates our failure to see the harm caused by animal farming.

By George Monbiot

the Guardian’s website

Eat less meat and fish, drink less milk. No request could be simpler, or more consequential. Nothing we do has greater potential for reducing our impacts on the living planet. Yet no request is more likely to elicit a baffled, hurt or furious response.

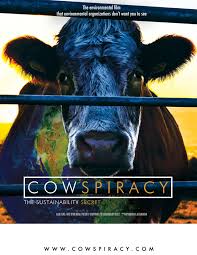

This point comes across with astonishing force in the film Cowspiracy. I would question some of the figures it uses, but its thesis – we just don’t want to talk about it – is undeniable. Leaders of the big US green groups either avoided the film makers like the plague or smiled and shook their heads when asked about livestock. State officials were struck dumb by the question.

Climate change, water use, forest destruction, river pollution, floods, dead zones in the sea: the impacts of animal farming are massive and global; in many cases greater than those of anything else we do. But we don’t want to know.

Livestock keeping is so embedded in our cultural and religious identity that to challenge it is, it seems, to attack the foundations of society. We like to see ourselves as free thinkers, but we all have our sacred cows.

The world’s great monotheistic religions arose among nomadic herders. While sedentary people worshipped a host of local gods, to the herders moving across the land, God was an overarching principle, often residing in the sky. The pastoral religions took root among settled peoples, and we found ourselves, even in wet and fertile lands like Britain, reciting the sere desert creeds of Abel’s profession, though we tilled the ground like Cain.

For millennia we counted our wealth in cattle (otherwise known as chattels, or stock). A literary tradition dating back to Theocritus, in the 3rd Century BC, portrays herding as a life of virtue and innocence, a refuge from the corruption and venality of the city. Two thousand years later, the trope persists almost nightly on television. You challenge these deep themes at your peril.

Look at the treatment of Kerry McCarthy, Labour’s new shadow environment secretary, who has the temerity to be vegan in a public place.

Among her many deadly sins are her proposal (before she became shadow minister) that meat should be treated “the same way as tobacco, with public campaigns to stop people eating it”, and her observation that – while other industries cut production when it exceeds demand – dairy farmers are exempt from market forces. They are paid to keep producing more milk than we want to drink.

Let’s focus on this point for a moment.

Four weeks ago, farmers from across Europe gathered in Brussels to protest against the law of supply and demand. Some of them explained their economic theories by throwing stones and bottles at the police and setting light to hay bales in the streets.

When other protesters expound their views this way, they are beaten up by the police, excoriated by the press and rewarded with accommodation in state facilities. In this case however, the European Commission gave them €500m to go away and not restructure their industry. This comes on top of the €55bn that farmers receive every year through the Common Agricultural Policy.

Before she became environment secretary in the Westminster government, Liz Truss founded the Conservative Party’s Free Enterprise Group, which believes that nothing should stand in the way of market forces, and prescribes the harshest medicine for those who live off the generosity of the state.

But last month she boasted that the UK had managed to secure £26 million of the new European handout: “the third largest [allocation] of all the member states.” Each dairy farmer, she exulted, would receive a state gift of, on average, £1,800.

The money isn’t allocated equally, by the way: it’s paid per litre of milk production. The bigger you are, the more you get, which is how the whole European subsidy system works.

Apart from rewarding the rich for being rich, there is not one element of the subsidy regime that accords with the beliefs Liz Truss professes. Yet, in over a year as environment secretary, I have never heard her mutter a word against it.

The justification given for this special treatment is that farming is an essential industry, and we must support it to secure food supplies. But its consistent problem is not undersupply but oversupply. Overproduction threatens our future food supply, as it accelerates the destruction of the soil. Dairy is more damaging than most sectors, as the cows are often fed on maize, the great soil-stripping crop.

A few days ago, I stumbled across one result of what we are paying for.

I had intended to spend the day beside the River Culm, that flows through the Blackdown Hills in Devon. It is supposed to be a wildlife haven, supporting brook lampreys, stone loach, wild trout and bullheads. A local primary school has been helping to restore the salmon population by hatching the fish and releasing them into the water.

Well, the river certainly made an impact – on my nostrils. I could smell it from 50 metres away. When I reached the bank, I saw that it had been reduced to little more than a farm sewer. It stank of cow manure. The bed was covered in feathery growths of “sewage fungus” (the name is misleading: in reality these are bacterial colonies). Here is a picture I took of it:

I’m told by an expert in river ecology that when sewage fungus becomes filamentous like this, it means that the pollution is both severe and chronic. This was the dominant lifeform. There was little life of other kinds to be seen.

So I changed my plans, and went to look for the cause of the pollution. Because the sewage fungus disappeared abruptly as I walked upstream, it was not hard to trace the apparent source. I found this pipe discharging cow slurry into the river:

Here is the slurry mingling with the bright river water:

The pipe came from a dairy farm on a hill overlooking the river. I went to take a look.

This is one of two indoor dairy units on the farm:

Here’s the first of the farm’s slurry lagoons, into which manure from the cattle flows:

This drains into a second lagoon:

Below the second lagoon, I found a trench containing a broken pipe. Running through the pipe – and past it – was a steady flow of stinking liquid manure:

This appeared to seep into a rivulet running off the land, that was thick with liquid slurry:

The stench was so bad that it almost made me gag. I followed this rivulet down to the pipe I had found, discharging into the river.

The weather had been dry for several days before my visit. I can only imagine what the flow must be like during a wet spell.

I phoned the Environment Agency’s number for reporting environmental destruction (it’s 0800 80 70 60: ring if you see something similar). Its inspectors visited the farm three days later.

I rang the farmer afterwards, but he said, “I’m not discussing it with you. It’s none of your business.” When I tried to ask questions, he hung up.

The Environment Agency told me it is “taking this incident seriously” and will decide what action to take according to what its investigations reveal. It said it is illegal to let slurry flow out of a lagoon into a ditch, and for a farm pipe to discharge into a river.

While the state of rivers in this country remains dire, as a result of our excessive use of water and of chronic, low-level contamination, the number of severe pollution incidents has declined in all sectors except one. Farming. In this case, it is rising.

Farming is now, by a long way, the nation’s leading cause of severe water pollution. And of all kinds of farming, dairy production causes the greatest number of serious incidents.

The scale of dairy farms has increased greatly in recent years, so when something goes wrong, it can go very wrong indeed.

Imagine how we would respond if this were any other industrial sector. If rivers like the Culm were frequently trashed by toxic sludge from factories, there would be an outcry. But, as Cowspiracy shows, the biggest problem is the one we don’t want to see.

Far from ensuring that such disasters cease, Liz Truss is deregulating the industry. She has called for “simpler and fewer farm inspections plus an overhaul of greening requirements”. She boasts that “since 2010 we have cut 10,000 unnecessary dairy inspections a year.” What she considers unnecessary, I see as an essential defence of the natural world.

The Environment Agency, through a series of devastating cuts, no longer has enough staff for the routine inspection of rivers. Now it’s up to you and I to report pollution, though we don’t possess its expertise. But if a river stinks, or you see something filthy running into it, call them.

Just as importantly, remember that we sit at the end of this chain of consequence, through our consumption. It’s true that our influence over the dairy sector is weaker than it might be, because of overproduction. But you can still make a difference, simply by reducing the animal products you put in your mouth. You might also do your waist a favour.

Should we not welcome this chance to change the world so swiftly and easily?

www.monbiot.com