Natasha Lennard

The Intercept

“YOU SEE THE train coming, but it hits you anyway,” said animal rights activist Josh Harper. “They just went down the list and it was ‘guilty as charged,’ ‘guilty as charged,’ ‘guilty as charged’ — every defendant, every count.” This is how, in the new documentary film “The Animal People,” Harper describes learning that he and his five co-defendants had been convicted on terrorism charges by a federal jury in 2006 for their involvement in animal rights struggle. The train was an apt metaphor for a case in which the government’s approach was indeed as grimly predictable as a commuter rail schedule, but nonetheless delivered a violent and shocking blow to the defendants, their movement, and those who believed in free speech rights in this country.

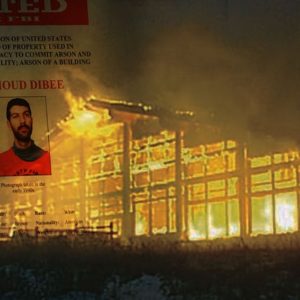

The convicted activists were members of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, known as SHAC, a decentralized animal rights movement that spread across the U.K. and U.S. from the late 1990s into the mid-2000s. The movement took aim at the notorious animal testing lab company Huntingdon Life Sciences, which did contract work for corporations. SHAC organized a potent direct-action campaign, which, at a number of points, threatened to shutter the huge testing corporation by driving investors to disaffiliate and divest. The tactics were diverse, from spreading information on animal cruelty, to holding demonstrations, to the occasional act of property damage. In response to SHAC activity, the FBI in 2005 deemed the animal liberation movement to be America’s No. 1 domestic terrorism threat. This, despite the fact that not a single human or animal was injured by SHAC activity in the country.

The convicted activists were members of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, known as SHAC, a decentralized animal rights movement that spread across the U.K. and U.S. from the late 1990s into the mid-2000s. The movement took aim at the notorious animal testing lab company Huntingdon Life Sciences, which did contract work for corporations. SHAC organized a potent direct-action campaign, which, at a number of points, threatened to shutter the huge testing corporation by driving investors to disaffiliate and divest. The tactics were diverse, from spreading information on animal cruelty, to holding demonstrations, to the occasional act of property damage. In response to SHAC activity, the FBI in 2005 deemed the animal liberation movement to be America’s No. 1 domestic terrorism threat. This, despite the fact that not a single human or animal was injured by SHAC activity in the country.

“The Animal People,” which is available on demand as of this week, focuses on the story of Harper and his co-defendants, all of whom were convicted under spurious charges of conspiracy to commit terrorism — though none of whom were found to have participated directly in any illegal acts. These were activists who attended raucous but legal protests, shared publicly available information about corporations on their website, and celebrated and supported militant actions taken in the name of the SHAC campaign. That is, they were convicted as terrorists for speech activity.

Each member of the so-called SHAC 7 — there were originally seven defendants before charges were dropped against one — has served their sentence and been out of prison for eight or more years. The broader militant campaign to close Huntingdon Life Science has long been inactive. Revisiting their case now, however, is a worthwhile exercise for understanding the extent to which the supposed rule of law can be bent in the interests of corporate power and its attendant servants in politics.

Each member of the so-called SHAC 7 — there were originally seven defendants before charges were dropped against one — has served their sentence and been out of prison for eight or more years. The broader militant campaign to close Huntingdon Life Science has long been inactive. Revisiting their case now, however, is a worthwhile exercise for understanding the extent to which the supposed rule of law can be bent in the interests of corporate power and its attendant servants in politics.

“The story that began to emerge was one of how corporations and the government circled their wagons to stop this campaign before it became a blueprint for other activist communities to apply in their own movements.”

The SHAC 7 case is a lesson in how legal instruments can be deployed to shut down dissent. At a time of renewed criminalization of protest activity nationwide, the so-called green scare stands as a worrying benchmark for the repression of political speech and the re-coding of protesters as criminals and terrorists. The capricious application of conspiracy charges — which we have seen recently deployed against protesters from Black Lives Matter advocates to Standing Rock water protectors — was mastered in the SHAC 7 prosecution. But “The Animal People” doesn’t only emphasize the excesses of the corporate-state power nexus; it recalls the passionate moral commitments of the SHAC members, and reminds us of a potent protest strategy and set of tactics, which I for one would happily see deployed again.

“We came across the story of the SHAC indictment and prosecution as we were researching another project and the high-level narrative as we understood it seemed so draconian — six activists indicted as terrorists for free speech activity,” Casey Suchan, the co-director of “The Animal People,” told me. “The SHAC campaign was strategic and effective and mobilized people globally. It nearly succeeded in shutting down the target of its campaign, Huntingdon Life Sciences, several times. The story that began to emerge was one of how corporations and the government circled their wagons to stop this campaign before it became a blueprint for other activist communities to apply in their own movements.”

THE FIRST HALF of the film traces the rise of what seemed, at certain times, to be an “unstoppable” movement. What began as a series of protests in the U.K. soon spread to the U.S., as activists in cities across the country took it upon themselves to confront Huntingdon-affiliated companies and shareholders. Some of the most committed organizers spent hours on complicated research into Huntingdon’s financial infrastructure, following the money to find any and every chokepoint on which to put pressure: be it the major banks and insurance firms propping up the company, or even the janitorial services contracted by a given Huntingdon lab. The information about potential targets was then shared on the SHAC website for activists to use as they saw fit.

The SHAC model, as it became known, worked by making the protests personal. Instead of simply marching in front of Huntingdon property, SHAC went to the homes, communities, and places of leisure frequented by people with even secondary connections to the testing lab. The goal was to make any association with Huntingdon intolerable. Time after time, it worked: According to SHAC, over 200 affiliates abandoned Huntingdon in response to their campaign; even the FBI claimed the number is over 100, stating, baselessly, that the other companies who disaffiliated at that time had other reasons.

“I understand why home demonstrations and personal targeting is so controversial,” Harper, a soft-spoken man with warm eyes, a round face, and “care” tattooed on his knuckles, explains on camera. “But when you take a billionaire like Warren Stephens” — an investment bank CEO — “he’s got this tremendous amount of comfort.” The activists then imposed themselves on the targets: “Every time he plays golf, there you are; when he goes out shopping, there you are; and when he comes home, there you are.”

SHAC tactics were, as any radical political experiment necessarily is, imperfect. Under the campaign’s banner, some activists exposed the names of children of targeted executives — an outlier action, to be sure, but one that visibly still haunts a number of the SHAC defendants in the documentary. The prosecution also made much of the publication on the SHAC website of such information, even though the defendants had no direct involvement. (In the only incident of human harm associated with the movement to shut Huntingdon down, U.K. activists at one point assaulted CEO Brian Cass.)

Skepticism also hovers around the decision to focus wholly on closing Huntingdon, given the prevalence of abusive animal testing. The idea had only been to start with the company, which had already come under public scorn following the release undercover video footage of animal abuse in their labs (parts of which are replayed in “The Animal People”). The activists had planned to win against HLS and expand from there; the biochemical and pharmaceutical industry, with the weight of the federal government behind them, ensured otherwise. Huntingdon has since changed its name to the banal and faux-Latinate “Envigo.”

“The Animal People” covers Stepanian’s youthful activism, his trial, and conviction, but does not include the fact that he spent the last five months of his three-year prison sentence inside a highly restrictive unit known as “Little Gitmo,” even though he had no significant disciplinary record. Stepanian’s brutal prison experience did not, however, lead him to disavow his activism or SHAC’s diversity of tactics. In “The Animal People,” we meet Stepanian as a doe-eyed punk kid, his car constantly running out of gas. He’s now a father, the founder of grassroots nonprofit Sparrow Media, and the vice president of Balestra Media, which advises progressive communications campaigns. And yet he’s no less doe-eyed, punk, or committed: “These tactics worked then, and they’ll work again,” he says in the documentary.

“The Animal People,” along with most every decent retelling of the SHAC 7 case, makes clear that the six individuals indicted on terror charges were fall guys in the government’s scrambling attempt to put a stop to a movement, which was, against all odds, bringing major corporations to heel. “Corporations get to do what they want — that’s a rule in our society,” Lauren Gazzola, a former SHAC 7 defendant with a robust knowledge of constitutional law, tells the filmmakers. “We challenged the right of this corporation to exist.”

THE STORY OF who gets to be a labeled a “terrorist” in this country reflects the ideological underpinnings behind government policy and law. Under the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, expanded in 2006 into the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, a terrorist is someone who intentionally damages or causes the loss of property — including freeing animals — used by the animal enterprise, or conspires to do so. It is an obscene state sanctification of corporate private property over life.

Given that the aim of any boycott or anti-corporate advocacy campaign is for the targeted corporation to incur losses, the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act sits at odds with the alleged constitutional protection of those activities. Without this terror statute in place, throwing bricks through windows, freeing test animals, or spray painting “puppy killer” on an executive’s car would still be a crime (though perhaps still morally justifiable). Labeling these acts as terrorism served to deter activists with hefty sentences and sway public opinion during the post-9/11 era of terror panic. The rhetorical shift justified extreme government tactics. According to investigative journalist Will Potter, who offers expert commentary throughout the documentary, at the time the FBI dedicated more wiretaps to SHAC than any other counterterrorism investigation in history. The activists were eventually arrested in their homes at gunpoint.

“The animal rights movement has really been the canary in the coal mine when it comes to modern government repression of activist campaigns.”

As I have written, the current pattern in law enforcement of labeling protests as “riots,” invoking slippery statutes of collective liability, and attempting to justify harsher crackdowns are all troubling for the same reason.

Over a decade after the SHAC trial, efforts from lawmakers like Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, to have “antifa” labeled a “terrorist organization” — despite not even being an organization — follow this frightening precedent. Meanwhile, the government’s successful use of conspiracy charges in the SHAC case made clear how far that legal doctrine can be stretched, even to the point of decimating First Amendment-protected speech.

The free speech issues at hand in the SHAC 7’s case are all the more stark given the government’s ongoing failure to address rampant, organized, and deadly white supremacist violence. While the courts said that the SHAC 7’s speech activity met the standard of “producing imminent lawless action,” organizers of the 2017 Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, explicitly planned online for their vile event to involve racist, fascist violence. The Unite the Right organizers’ speech, it seems, did not meet the “imminence” standard that was set so low in the case of animal rights supporters.

That’s not an argument for more use of the conspiracy doctrine. Instead, it shows the importance of Gazzola’s statement in “The Animal People” that the First Amendment is a rule, and “if the law is an instrument of power, it doesn’t matter what the rules say.” This was true long before the Trump era but grows ever more pernicious in the face of a government driven towards fascistic nationalism and pushing in far-right federal judges.

“The animal rights movement has really been the canary in the coal mine when it comes to modern government repression of activist campaigns,” the film’s co-director Denis Henry Hennelly told me by email. The sentiment was echoed by Potter, the journalist. “This is the new playbook for the criminalization of dissent,” he told me. “I’ve already seen it applied to other social movements, both here in the U.S. and internationally. In the years since the trial, though, it has only become more prescient.”

FOR VIEWERS WITH little to no knowledge of this history of animal liberation struggle and its repression, “The Animal People” offers a compelling primer, organized through archival protest footage, old home videos of some of the SHAC 7 defendants, interviews with legal experts and investigative journalists, one smug businessman who was targeted by a SHAC campaign, and more recent interviews with the former defendants. As with any 90-minute film, the story the directors, Suchan and Hennelly, chose to tell is only one slice of an international and dispersed movement’s history. But for a documentary with some Hollywood backing — animal lover Joaquin Phoenix is an executive producer — “The Animal People” stands uncomplicatedly on the side of the SHAC defendants and doesn’t dampen their anti-capitalist message.

For Stepanian, this element of animal liberation and the necessary connection with anti-capitalist environmental activism can’t be forgotten. “In terms of the direct-action animal liberation movement today, it’s largely impotent compared to the time period of the SHAC campaign, because most messaging falls squarely in what is safe within the framework of capitalism: Much of the activity revolves around better consumer choices,” Stepanian told me. “I’d like to see another campaign with a lens critical of capitalism, which understands that it is this socioeconomic system which rewards the worst practices when it comes to the treatment of animals as resources, and rewards rapacious attitudes towards the environment.”

The film closes with a montage of uprisings, from students in Hong Kong, to the gilets jaunes in France, to Black Lives Matter activists in the U.S., and marchers for liberation in Palestine. It’s a minimal gesture toward intersectionality in a film that underplays the aspects of SHAC that were dedicated to shared struggle. “It’s not OK to be singular in your solidarity; justice and liberation for all life is paramount,” Stepanian told me, recalling how, prior to his indictment, he went on two organizing road trips with former Black Liberation Army member Ashanti Alston. “We are all intersectional activists,” he said of his former co-defendants.

Jake Conroy of the SHAC 7, who joined one of the road trips, comments near the film’s end: “It’s not just about earth liberation, it’s not just about human liberation, and it’s not just about animal liberation. It’s about collective liberation.”