FBI agents are devoting substantial resources to a multistate hunt for two baby piglets that the bureau believes are named Lucy and Ethel. The two piglets were removed over the summer from the Circle Four Farm in Utah by animal rights activists who had entered the Smithfield Foods-owned factory farm to film the brutal, torturous conditions in which the pigs are bred in order to be slaughtered.

While filming the conditions at the Smithfield facility, activists saw the two ailing baby piglets laying on the ground, visibly ill and near death, surrounded by the rotting corpses of dead piglets. “One was swollen and barely able to stand; the other had been trampled and was covered in blood,” said Wayne Hsiung of Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), which filmed the facility and performed the rescue. Due to various illnesses, he said, the piglets were unable to eat or digest food and were thus a fraction of the normal weight for piglets their age.

Rather than leave the two piglets at Circle Four Farm to wait for an imminent and painful death, the DxE activists decided to rescue them. They carried them out of the pens where they had been suffering and took them to an animal sanctuary to be treated and nursed back to health.

This single Smithfield Foods farm breeds and then slaughters more than 1 million pigs each year. One of the odd aspects of animal mistreatment in the U.S. is that species regarded as more intelligent and emotionally complex — dogs, dolphins, cats, primates — generally receive more public concern and more legal protection. Yet pigs – among the planet’s most intelligent, social, and emotionally complicated species, capable of great joy, play, love, connection, suffering and pain, at least on a par with dogs — receive almost no protections, and are subject to savage systematic abuse by U.S. factory farms.

At Smithfield, like most industrial pig farms, the abuse and torture primarily comes not from rogue employees violating company procedures. Instead, the cruelty is inherent in the procedures themselves. One of the most heinous industry-wide practices is one that DxE activists encountered in abundance at Circle Four: gestational crating.

Where that technique is used, pigs are placed in a crate made of iron bars that is the exact length and width of their bodies, so they can do nothing for their entire lives but stand on a concrete floor, never turn around, never see any outdoors, never even see their tails, never move more than an inch. That was the condition in which the activists found the rotting piglet corpses and the two ailing piglets they rescued.

Female pigs give birth in this condition. They are put in so-called farrowing crates when they give birth, and their piglets run underneath them to suckle and are often trampled to death. The sows are bred repeatedly this way until their fertility declines, at which point they are slaughtered and turned into meat.

The pigs are so desperate to get out of their crates that they often spend weeks trying to bite through the iron bars until their gums gush blood, bash their heads against the walls, and suffer a disease in which their organs end up mangled in the wrong places, from the sheer physical trauma of trying to escape from a tiny space or from acute anxiety (called “organ torsion”).

So cruel is the practice that in 2014, Canada effectively banned its usage, as the European Union had done two years earlier. Nine U.S. states, most of which host very few farms, have banned gestational crating (in 2014, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, with his eye on the GOP primary in farm-friendly Iowa, vetoed a bill that would have made his state the 10th).

But in the U.S. states where factory farms actually thrive, these devices continue to be widely used, which means a vast majority of pigs in the U.S. are subjected to them. The suffering, pain, and death these crates routinely cause were in ample evidence at Smithfield Foods, as accounts, photos, and videos from DxE demonstrate.

FBI raids animal sanctuaries

Under normal circumstances, a large industrial farming company such as Smithfield Foods would never notice that two sick piglets of the millions it breeds and then slaughters were missing. Nor would they care: A sick and dying piglet has no commercial value to them.

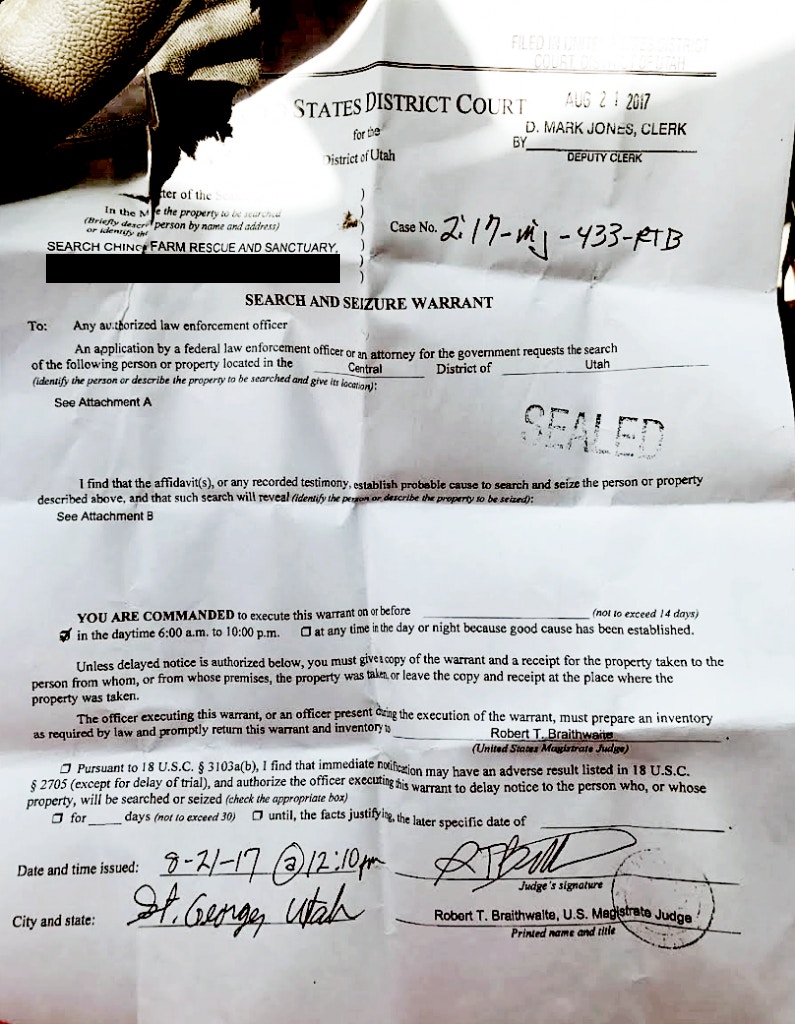

Yet the rescue of these two particular piglets has literally become a federal case — by all appearances, a matter of great importance to the Department of Justice. On the last day of August, a six-car armada of FBI agents in bulletproof vests, armed with search warrants, descended upon two small shelters for abandoned farm animals: Ching Farm Rescue in Riverton, Utah, and Luvin Arms in Erie, Colorado.

These sanctuaries have no connection to DxE or any other rescue groups. They simply serve as a shelter for sick, abandoned, or otherwise injured animals. Run by a small staff and a team of animal-loving volunteers, they are open to the public to teach about farm animals.

The attachments to the search warrants specified that the FBI agents could take “DNA samples (blood, hair follicles or ear clippings) to be seized from swine with the following characteristics: I. Pink/white coloring; II. Docked tails; III. Approximately 5 to 9 months in age; IV. Any swine with a hole in right ear.”

The FBI agents searched the premises of both shelters. They demanded DNA samples of two piglets they said were named Lucy and Ethel, in order to determine whether they were the two ailing piglets who had been rescued weeks earlier from Smithfield.

A representative of Luvin Arms, who insisted on anonymity due to fear of the pending criminal investigation, described the events. The FBI agents ordered staff and volunteers to stay away from the animals and then approached the piglets. To obtain the DNA samples, the state veterinarians accompanying the FBI used a snare to pressurize the piglet’s snout, thus immobilizing her in pain and fear, and then cut off close to two inches of the piglet’s ear.

The piglet’s pain was so severe, and her screams so piercing, that the sanctuary’s staff members screamed and cried. Even the FBI agents were so sufficiently disturbed by the resulting trauma, that they directed the veterinarians not to subject the second piglet to the procedure. The sanctuary representative recounted that the piglet who had part of her ear removed spent weeks depressed and scared, barely moving or eating, and still has not fully recovered. The FBI “receipt” given to the sanctuaries shows they took DNA samples “from swine.”

Several volunteers at one of the raided animal shelters said they were followed back to their homes by FBI agents, who dramatically questioned them in front of family members and neighbors. And there is even reason to believe that the bureau has been surveilling the activists’ private communications regarding the rescue of this piglet duo.

The FBI specified as part of its search that it was seeking DNA samples from piglets they said were named “Lucy” and “Ethel.” But those were not the names the activists used when publicly discussing the rescue of the two piglets. In their videos about the rescue, they called the pair “Lily” and “Lizzie.” Lucy and Ethel were code names the activists used internally, suggesting that agents were surveilling the activists’ communications — either electronically or through informants — in an effort to find the two piglets and build a criminal case against the group.

Subsequent events confirmed that this show of FBI force was designed to intimidate the sanctuaries, which played no role in the rescue. Weeks after the FBI’s execution of the two search warrants, Luvin Arms — in the midst of an interview with The Intercept — received a telephone call from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, claiming the agency had received “a complaint” that the sanctuary lacked the legally required licenses for animal shelters that are open to the public. “We had never had an FBI visit or a USDA call about licenses, and now suddenly, within weeks, both happened,” the sanctuary representative said.

Retaliation for exposing cruel treatment

What has vested these two piglets with such importance to the FBI is that their rescue is now part of what has become an increasingly visible public campaign by DxE and other activists to highlight the barbaric suffering and abuse that animals endure on farms like Circle Four. Obviously, the FBI and Smithfield — the nation’s largest industrial farm corporation — don’t really care about the missing piglets they are searching for. What they care about is the efficacy of a political campaign intent on showing the public how animals are abused at factory farms, and they are determined to intimidate those responsible.

Deterring such campaigns and intimidating the activists behind them is, manifestly, the only goal here. What made this piglet rescue particularly intolerable was an article that appeared in the New York Times days after the rescue, which touted the use of virtual reality technology by animal rights activists to allow the public to immerse in the full experience of seeing what takes place in these companies’ farms. The article featured a photograph of the DxE activists rescuing the piglets from the Smithfield farm:

The Times article was published July 6. The search warrant against the sanctuaries was obtained the following month, in mid-August, and then executed on August 31. In the interim, the piglets had become stars of a clearly effective campaign against Smithfield Foods.

In response to questions from The Intercept, Smithfield insisted that it does not abuse its animals. But, as is typical for factory farms, the company offered little more then generalized denials, accompanied by vague accusations that the videos and photos the activists took are somehow “distorted.”

After they rescued the two piglets, the DxE activists did not try to hide what they had done: They did the opposite. They used a tactic known as “open rescue,” the purpose of which is to publicly detail what has been done to help the public understand the true nature of the abuses.

The activists wrote about the rescue in social media postings that went viral, detailing the horrific conditions they witnessed at Smithfield and describing the suffering of the piglets. They posted videos to Facebook and YouTube that they filmed of the farm and the rescue as it happened, with other videos showing Lily and Lizzie being treated at the sanctuaries and growing into happy, playful, healthy adolescents.

Video: Direct Action Everywhere

Plainly, the “crime” of these activists that has galvanized the FBI is not the “theft” of two dying piglets; it is political activism and investigative journalism, which exposes the cruelty and abuse at the heart of this powerful industry.

In response to a few media reports on the FBI raids at the sanctuaries, bureau spokesperson Sandra Barker told the Washington Post: “I can say that we were at the two locations conducting court-authorized activity related to an ongoing investigation. Because it’s ongoing, I’m not able to provide any more details at this time.”

To an industry feeling endangered by growing public disgust over conditions at industrial farms — driven by scandals within the meat, pork, and poultry sectors — Lily and Lizzie are political and journalistic threats. Animals like them are vital for enabling animal rights activists to demonstrate to the public in a visceral, personalized way that this industry generates massive profit by monstrously and unnecessarily torturing living beings who are emotionally complex and experience great suffering.

Government power abused to intimidate and punish activists

The Justice Department’s grave attention to a case of two missing piglets reflects how vigilantly the U.S. government uses extreme measures to protect the agricultural industry — not from unjust economic loss, violent crime, or theft, but from political embarrassment and accurate reporting that damages the industry’s reputation.

A sweeping framework of draconian laws — designed to shield the industry from criticism and deter and punish its critics — has been enacted across the country by federal and state legislatures that are captive to the industry’s high-paid lobbyists. The most notorious of these measures are the “ag-gag” laws, which make publishing videos of farm conditions taken as part of undercover operations a felony, punishable by years in prison.

Though many courts, including most recently a federal court in Utah, have struck down these laws as an unconstitutional assault on speech and press freedoms, they continue to be used in numerous states to harass and, in some cases, prosecute animal rights activists. As the Times article notes, these ag-gag laws are one reason activists are forced to turn to virtual reality: to show what really happens inside industrial farms without running the risk of prosecution.

Many mother pigs had nipples that were torn into bloody shreds from feeding starving piglets.

Photo: Wayne Hsiung/DxE

Even more extreme and menacing is the federal Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act. As I described previously when reporting on the arrest of two young activists — who faced 10 years in prison for freeing minks from farm cages before the animals could be sliced to death and turned into luxury coats — nonviolent animal rights activists are often designated as “terrorists” under the AETA and are treated in the court system as such, even when no human beings are hurt and the economic loss is minimal:

As is typical for lobbyist and industry-supported bills, the AETA passed with overwhelming bipartisan support (its two prime Senate sponsors were James Inhofe, R-Okla., and Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif.) and then was signed into law by George W. Bush.

This “terrorism” law is violated if one “intentionally damages or causes the loss of any real or personal property (including animals or records) used by an animal enterprise … for the purpose of damaging or interfering with” its operations. If you do that — and note that only “damage to property” but not to humans is required — then you are guilty of “domestic terrorism” under the law.

Prior to the 2006 enactment of the AETA, animal rights activism that damaged property was already illegal under a 1992 federal law, as well as various state laws, and subject to severe punishments. The primary purpose of the new 2006 law was to expand the scope of criminal offenses to include plainly protected forms of political protest, and to heighten the legal punishments and intensify social condemnation by literally labeling animal-rights activists as “domestic terrorists.”

The factory farm industry and its armies of lobbyists wield great influence in the halls of federal and state power, while animal rights activists wield virtually none. This imbalance has produced increasingly oppressive laws, accompanied by massive law enforcement resources devoted to punishing animal activists even for the most inconsequential nonviolent infractions — as the FBI search warrant and raid in search of “Lucy and Ethel” illustrates.

The U.S. government, of course, has always protected and served the interests of industry. Beginning when most of the nation was fed by small farms, federal agencies have been particularly protective of agricultural industry. That loyalty has only intensified as family farms have nearly disappeared, replaced by industrial factory farms where animals are viewed purely as commodities, instruments for profit, and treated with unconstrained cruelty.

Lately, opposition is emerging from unusual places. Utah federal judge Robert J. Shelby, an Obama appointee who is a lifelong Republican, recently struck down the state’s ag-gag law on First Amendment grounds, noting in his ruling:

For as long as farmers have put food on American tables, the government has endeavored to support and protect the agricultural industry. … In short, governmental protection of the American agricultural industry is not new, and has taken a variety of forms over the last two hundred years. What is new, however, is the recent spate of state laws that have assumed an altogether novel approach: restricting speech related to agricultural operations.

As Shelby detailed, those ag-gag laws were not used until activists began having success in showing the public the true extent of cruelty that industrial farms impose on animals:

Nobody was ever charged under these [early ag-gag] laws, and for nearly two decades no new ag-gag legislation was introduced. That changed, however, after a series of high profile undercover investigations were made public in the mid to late 2000s.

To name just a few, in 2007, an undercover investigator at the Westland/Hallmark Meat Company in California filmed workers forcing sick cows, many unable to walk, into the “kill box” by repeatedly shocking them with electric prods, jabbing them in the eye, prodding them with a forklift, and spraying water up their noses. A 2009 investigation at Hy-Line Hatchery in Iowa revealed hundreds of thousands of unwanted day-old male chicks being funneled by conveyor belt into a macerator to be ground up live.

That same year, undercover investigators at a Vermont slaughterhouse operated by Bushway Packing obtained similarly gruesome footage of days-old calves being kicked, dragged, and skinned alive. A few years later, an undercover investigator at E6 Cattle Company in Texas filmed workers beating cows on the head with hammers and pickaxes and leaving them to die. And later that year, at Sparboe Farms in Iowa, undercover investigators documented hens with gaping, untreated wounds laying eggs in cramped conditions among decaying corpses.

The publication of these and other undercover videos had devastating consequences for the agricultural facilities involved. The videos led to boycotts of facilities by McDonald’s,Target, Sam’s Club, and others. They led to bankruptcy and closure of facilities and criminal charges against employees and owners. They led to statewide ballot initiatives banning certain farming practices. And they led to the largest meat recall in United States history, a facility’s entire two years’ worth of production. Over the next three years, sixteen states introduced ag-gag legislation.

In other words, both the legislative process and law enforcement agencies are being blatantly exploited — misused — to protect not the property rights but the reputational interests of this industry. Having the FBI — in the midst of real domestic terrorism threats, hurricane-ravaged communities, and intricate corporate criminality — send agents around the country to animal sanctuaries in search of DNA samples for two missing piglets may seem like overkill to the point of being laughable. But it is entirely unsurprising in the context of how law enforcement resources are used, and on whose behalf.

Smithfield Food’s defenses

It makes sense that Smithfield Foods would be petrified of the public learning of many of its practices. But in this particular case, they are specifically trying to hide the pure evils of gestational crates. This video, taken by an investigator with the Humane Society in 2012, shows the widespread but hideous reality of gestational crates at a Smithfield farm:

In response to the public controversy over this practice, generated by activists filming what was going on, Smithfield announced in 2012 that they would phase out gestational crating in 10 years — by 2022. They then claimed that by the end of 2017, they would transition completely to “group housing systems.” But as the DxE videos show, gestation crates are exactly what activists found in abundance when they visited Smithfield’s Circle Four.

Indeed, when Wayne Hsiung and DxE visited Circle Four over the summer, they saw no signs whatsoever of any construction or reform efforts to move away from gestational crates, Hsiung told the Intercept. As the videos show, Circle Four had thousands of pigs suffering in such crates. That was where the activists found the two piglets, close to death.

When Smithfield learned that The Intercept was reporting on these issues, a spokesperson emailed a statement and invited further questions. The statement claims that in response to DxE’s reporting, Smithfield “immediately launched an investigation and completed a third-party audit,” and “the audit results show no findings of animal mistreatment.”

This is a typical industry tactic: When they claim, as they almost always do, that their paid auditors discovered “no findings of animal mistreatment,” what they mean is that there was no evidence that their employees engaged in activities that corporate procedures explicitly prohibit (such as beating the animals or administering electric shock).

But what the audit does not do is ask whether the procedures themselves (such as gestational crating) are abusive and thus constitute “mistreatment.” Smithfield failed to provide a response to The Intercept’s follow-up questions about what it does and does not mean when their auditors claim no “mistreatment” was discovered; the company simply reiterated that “the animals observed on the farm by the audit team were in good condition, appeared comfortable, free of clinical disease, and showed no signs of fear or intimidation in the presence of people.” Simply review the DxE video above, and the featured photos showing what they found at Circle Four, to judge for yourself.

Cramped conditions lead to many pigs being trampled to death at Smithfield-owned Circle Four Farm in Utah.

Photo: Wayne Hsiung/DxE

In its statement, Smithfield also accused the activists who rescued the two piglets of “risk[ing] the life of the animals they stole and the lives of the animals living on our farms by trespassing” — an odd claim from a company that plans to slaughter all of those same animals. When asked to specify how the activists endangered the lives of the sick animals they rescued, Smithfield told The Intercept that “the video’s creators violated Smithfield’s strict biosecurity policy, which prevents the spread of disease on farms.” The statement added: “The piglets were not ‘extremely ill’ or ‘on the verge of death.’ These piglets, along with other animals living on the farm, are well cared for throughout their lifetime.”

But in response, Hsiung told the Intercept: “Our activists use better biosecurity protocols than the company’s own employees, as evidenced by the dead, rotting piglets on the farm. Allowing baby animals to rot to death is, in fact, a serious violation of biosecurity and food safety. Taking photographs of animal cruelty is not.”

Smithfield also accused the activists of manipulating their film, claiming that “the video appears to be highly edited and even staged in an attempt to manufacture an animal care issue where one does not exist.” But Smithfield did not respond to this question from The Intercept about the staging allegation: “How would these activists stage hundreds of pigs in gestation crates and dozens of piglets rotting to death — all in virtual reality, no less? It would take a Hollywood blockbuster budget and the most sophisticated team of computer-generated imagery for that. What’s Smithfield’s theory about what they fabricated in this video?”

The only specifics Smithfield offered was the assertion that “based on the review of animal care experts, it appears piglets were moved from one section of the barn to another to support the inaccuracies and falsehoods described in the video by its creators.”

But Hsiung said: “The video speaks for itself. I don’t know how we can fake a rotting piglet.” Regarding the accusation that they moved piglets, he added: “I imagine what they are seeing is piglets in the wrong sort of pen, gestation rather than farrowing. But that is a testament to their own failed animal care practices. We were shocked and horrified, as well, to see piglets born and housed in inappropriate conditions that left them exposed to trauma.”

In sum, the industry has long responded to these videos — which they tried in the first instance to use their lobbying power to criminalize — by insisting that the videos are distorted. Yet they never specify what these supposed distortions are. Now that activists are using virtual reality technology, which allows the viewer to see everything the activists see, such claims are even more untenable than they were before.

Revolving door with agribusiness

A recent change in U.S. political discourse — spurred by events such as the 2008 financial crisis, the Occupy movement, and the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign — is the increasingly common use of the words “oligarchy” and “plutocracy” to describe the country’s political system. Though dramatic, the terms, melded together, describe a fairly simple and common state of affairs: power exerted by and exercised for the exclusive benefit of a small group of people who wield the greatest financial power.

It is hard to imagine a more vivid illustration than watching FBI agents don bulletproof vests and execute DNA search warrants for Lily and Lizzie, all to deter and intimidate critics of a savage industry that funds politicians and the lobbyists that direct them.

Substantial attention has been paid over the last several years to the “revolving door” that runs Washington — industry executives being brought in to run the agencies that regulate their industries, followed by them returning to that industry once their industry-serving government work is done. That’s how Wall Street barons come to “regulate” banks, how factory owners come to “regulate” workplace safety laws, how oil executives come to “regulate” environmental protections — only to leave the public sector and return back to lavish rewards from those same industries for a job well done.

Though it receives modest attention, this revolving door spins faster, and in more blatantly sleazy ways, when it comes to the USDA and its mandate to safeguard animal welfare. The USDA is typically dominated by executives from the very factory farm industries that are most in need of vibrant regulation.

For that reason, animal welfare laws are woefully inadequate, but the ways in which they are enforced is typically little more than a bad joke. Industrial farming corporations like Smithfield know they can get away with any abuse or “mislabeling” deceit (such as misleading claims about their treatment of animals) because the officials who have been vested with the sole authority to enforce these laws — federal USDA officials — are so captive to their industry. Courts have repeatedly ruled that private individuals, animal rights groups, and even state authorities have no right to sue to enforce animal welfare laws, because the “exclusive authority” lies with the U.S. government, which has no real interest in actually enforcing those laws.

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue on July 12, 2017, in Atlanta.

Photo: Bob Andres/Atlanta Journal-Constitution/AP

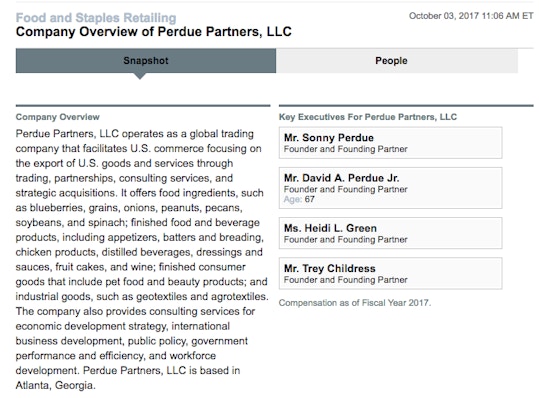

The current secretary of agriculture, former Georgia Gov. Sonny Perdue (pictured, right), is just one example, but he vividly highlights the revolving door form of legalized corruption that dominates this industry.

Perdue was raised on a Georgia row farm and obtained his doctorate in veterinary medicine. Despite those seemingly benign credentials, the factory farm industry celebrated the news of his nomination by President Donald Trump. The National Chicken Council, for instance, demanded that he be “confirmed expeditiously.” The enthusiasm was for good reason.

“Georgia was pretty friendly to food-industry interests during Perdue’s two terms,” Grub Street reported, and Perdue “took about $330,000 in contributions from Monsanto and other agribusinesses for his campaigns.” In 2009, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, the lobbying group for genetically modified foods, named Perdue its “Governor of the Year” because, it said, “he has been a stalwart advocate of the biosciences in Georgia and truly understands the promise of our industry.” As Georgia governor, Perdue supported the rapid expansion of factory farm giant Perdue Farms (to which he has no familial relation), with its long history of allegations of animal abuse.

And Perdue has extensive ties to the agribusiness sector he’s now supposed to oversee and regulate. The firm of which he is the founding partner and his family owns and runs, Perdue Partners LLC, is an agribusiness at the heart of this industry:

After being confirmed, Perdue wasted little time lavishing his agribusiness industry with gifts. In February, the USDA “abruptly removed inspection reports and other information from its website about the treatment of animals at thousands of research laboratories, zoos, dog breeding operations and other facilities,” reported the Washington Post. Then, two senators who have received large sums from farmers and ranchers — Democrat Debbie Stabenow and Republican Pat Roberts — agitated for the recession of the Obama administration’s mild regulations on organic eggs, designed to improve conditions for chickens, and the Perdue-led USDA “put the new standard on hold and suggested that it might even be withdrawn.”

In sum, with industry insiders dominating the sole agency (USDA) with the authority to regulate factory farms, animals that are captive, abused, tortured, and slaughtered en masse have little chance, even when it comes to just applying existing laws with a minimal amount of diligence. The politics of the U.S. — including the fact that a key farm state, Iowa, plays such a central role in presidential elections — means there are massive forces arrayed behind factory farms, and very few in support of animal welfare.

From fringe to the mainstream

But the animal rights movement, despite receiving relatively scant media attention and operating under the threat of federal prosecutions for terrorism, boasts some of the nation’s more effective, shrewd, and tenacious political activists. They have made significant strides in turning the public against the worst of the prevailing practices on these farms, and more generally, in forcing into the public consciousness the knowledge of how this industry imposes suffering, abuse, and torture on living beings on a mass and systematic scale, all to maximize profits.

Just a decade ago, the cause of animal cruelty and exploitation was a fringe position, rarely appearing outside far-left circles. That has all changed, thanks largely to the efforts of these activists, many of whom have been imprisoned for their efforts. Most activists say that it was unimaginable even a decade ago for major newspaper columnists such as the New York Times’ Nicholas Kristof or Frank Bruni to take up their cause, yet that’s precisely what they have done in a series of columns over the last several years.

“If you torture a single chicken and are caught, you’re likely to be arrested. If you scald thousands of chickens alive, you’re an industrialist who will be lauded for your acumen,” Kristof wrote in one 2015 column. He described the savagery of the process used to slaughter chickens by the millions and scornfully dismissed industry’s claim that no abuse or mistreatment was found by their auditors.

In a column the year before, Kristof detailed the barbarism and misleading claims that chickens are “humanely raised” at Perdue Farms — the company USDA Secretary Perdue helped to expand — and concluded: “Torture a single chicken and you risk arrest. Abuse hundreds of thousands of chickens for their entire lives? That’s agribusiness.”

And that’s to say nothing of the other significant costs from industrial farming. There are serious health risks posed by the fecal waste produced at such farms. And the excessive, reckless use of antibiotics common at factory farms can create treatment-resistant bacterial strains capable of infecting and killing humans. There is also increasing awareness that industrial farming meaningfully exacerbates climate problems, with some research suggesting that it produces more greenhouse gas emissions than all forms of transportation combined. Reviewing the meat industry in 2014, Kristof summarized what he learned this way:

Our industrial food system is unhealthy. It privatizes gains but socializes the health and environmental costs. It rewards shareholders — Tyson’s stock price has quadrupled since early 2009 — but can be ghastly for the animals and humans it touches.

Bruni wrote in a 2014 column headlined “According Animals Dignity” of “a broadening, deepening concern about animals that’s no longer sufficiently captured by the phrase ‘animal welfare.’” Instead of simply curbing the most egregious abuses, he wrote, a more principled awareness of the intrinsic worth and rights of animals is emerging: “an era of what might be called animal dignity is upon us.”

Some progress is indeed undeniable. Laws are being re-written to recognize that dogs and other pets are more than property; places such as Sea World and Ringling Brothers’ circuses can no longer feature imprisoned animals forced to perform; and some states are enacting laws criminalizing the worst extremes of animal cruelty.

One U.S. Senator, Democrat Cory Booker of New Jersey, has placed animal rights protections as one of his legislative priorities. Booker, who has been a vegetarian since college and recently announced his transition to full veganism, has sponsored a spate of bills to fortify the rights of animals: from banning the selling of shark fins to limiting the legal uses of animals for testing to requiring humane treatment of animals in all federal facilities.

While he has been attacked by the New York Post for “animal rights extremism” after he announced his veganism, Booker now regularly and unflinchingly invokes the core principles of animal rights: “I want to try to live my own values as consciously and purposefully as I can. Being vegan for me is a cleaner way of not participating in practices that don’t align with my values.” Rather than these legislative efforts being scorned, a spokesman for Booker told the Intercept that “Sens. Merkley and Whitehouse have been reliable allies on animal testing and other efforts; the Shark Fin effort has a number of cosponsors as well; and Sens. Schatz, Markey, Warren, Feinstein, Blumenthal have been partners as well.”

The devastating cost of industrial farming and the mass torture and slaughter on which it depends — moral, spiritual, physical, environmental — are being documented in scholarly circles with increasing clarity. A group of public health specialists jointly wrote in a New York Times op-ed in May: “This sweeping change in meat production and consumption has had grave consequences for our health and environment, and these problems will grow only worse if current trends continue.”

In general, the core moral and philosophical question at the heart of animal rights activism is now being seriously debated: Namely, what gives humans the right or justification to abuse, exploit, and torture non-human species? If there comes a day when some other species (broadly defined) — such as machines — surpass humans in intellect and cognitive complexity, will they have a valid moral claim to treat humans as commodities whose suffering and death can be assigned no value?

The irreconcilable contradiction of lavishing love and protection on dogs and cats, while torturing and slaughtering farm animals capable of a deep emotional life and great suffering is becoming increasingly apparent. British anthropologist Jane Goodall, in her groundbreaking book “The Inner World of Farm Animals,” examined the science of animal cognition and concluded: “Farm animals feel pleasure and sadness, excitement and resentment, depression, fear, and pain. They are far more aware and intelligent than we ever imagined … They are individuals in their own right.”

All of these changes have been driven by animal rights activists who, often at great risk to themselves, have forced the public to be aware of the savagery and cruelty supported through food consumption choices. That’s precisely why this industry is so obsessed with intimidating, threatening, and outlawing this form of activism: because it is so effective.

Dissidents are tolerated to the extent they remain ineffectual and unthreatening. When they start to become successful — that is, threatening to powerful interests — the backlash is inevitable. The tools used against them are increasingly extreme as their success grows.

To call the FBI’s actions in raiding these animal sanctuaries a profound waste of its resources is both an understatement and beside the point. The real short-term goal is to target those most vulnerable — volunteer-supported animal shelters — to scare them out of taking care of rescued animals. And the ultimate goal is to fortify and intensify a climate of intimidation and fear designed to deter animal rights activists from reporting on the horrifying realities of these factory farms.

There is a temptation to turn away from and ignore this mass suffering and cruelty because it’s so painful to confront, so much more pleasant to remain unaware of it. Animal rights activists are determined to prevent us from doing so, and we should all feel gratitude for their increasing success in making us see what we are enabling when we consume the products of this barbaric and sociopathic industry.

Top photo: Two dying piglets were rescued by Direct Action Everywhere activists from cruel conditions — where they were left to suffer to death — at Smithfield-owned Circle Four Farm in Utah.

Contact the author: