His book, “The Case for Animal Rights,” is recognized as a groundbreaking text in the field of applied ethics.

His book, “The Case for Animal Rights,” is recognized as a groundbreaking text in the field of applied ethics.

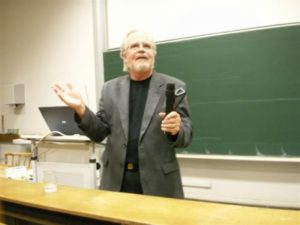

Tom Regan, an American moral philosopher known for his groundbreaking work in the study of animal rights, died of pneumonia Friday, Feb. 17. He was 78.

A professor emeritus at North Carolina State University, Regan was one of the rare philosophers whose work had import and influence outside academia. The former butcher became a vegan and a historic figure in the animal rights movement.

Though he wrote many books and papers, his most notable work was “The Case for Animal Rights,” published in 1983 near the beginning of the modern animal movement. A monument in the history of animal rights philosophy, it sparked much subsequent debate and was translated into multiple languages.

It is widely recognized as a classic text, but the book has been somewhat overshadowed for popular audiences by its predecessor, “Animal Liberation,” the 1975 book by Australian philosopher Peter Singer.

Singer was one of the first to eulogize Regan, tweeting Friday afternoon, “I’ve just heard that sad news that Tom Regan, a philosophical pioneer for animals who I have known since 1973, died this morning.”

As peers and collaborators, they sparred intellectually over ideas.

Their most central disagreement rested on the nature of “rights,” a term frequently taken for granted. And this disagreement set “The Case for Animal Rights” apart from previous work.

In writing a case for animal rights, Regan was not simply adopting the language of other moral and political movements: civil rights, human rights, women’s rights. He was distinguishing his view from that of Singer and similar thinkers, known as utilitarians, who reject the notion of “rights” as a conceptual matter.

Utilitarians argue that certain features of the world, such as pain and pleasure, joy and suffering, are good or bad. The right thing to do, utilitarians tell us, is to maximize the amount of good in the world and minimize the amount of bad. They deny that morality is about “rights” — though protecting legal rights to property and freedom, for instance, may be prudent or wise in their view.

Philosophers like Regan have argued that this is wrong. There are certain rights that should not be violated, even if it would make the world as a whole better off. For example, these philosophers might argue that it would be wrong to imprison a wrongly accused woman, even if the suffering imposed on her would be outweighed by the public’s desire to see her behind bars.

Regan’s revolutionary argument was that rights — in particular, the right not to be killed — could be sensibly applied to animals.

Many had argued, and many continue to argue, that because animals cannot have responsibilities, they therefore cannot be said to have rights, even if we should not be gratuitously cruel to them.

But Regan pointed out that most people believe babies have rights, even though they cannot have responsibilities.

He also argued that conceptually, having a right does not require the possibility of having responsibilities. All that rights require is being a “subject-of-a-life.” According to The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy, Regan defined his term thus: “Subjects-of-a-life are characterized by a set of features including having beliefs, desires, memory, feelings, self-consciousness, an emotional life, a sense of their own future, an ability to initiate action to pursue their goals, and an existence that is logically independent of being useful to anyone else’s interests.”

By arguing that animals could have rights, Regan staked out a position that was in some ways more radical than Singer’s.

While Singer’s utilitarian view is often taken as an argument that we should reduce the pain animals suffer and make their lives in our care as pleasant as possible, Regan’s argument for animal rights implies that most if not all human use of animals is unjustifiable, which is why he was a vegan.

The rights argument also makes a clear case against experimentation on animals, because scientific benefits provided to humans would not excuse the violation of animal rights.

Some animal rights advocates believed Regan’s work did not go quite far enough. His definition of subject-of-a-life was quite detailed and demanding, and while it includes many animals, it’s not entirely clear which species it excludes. Other philosophers have argued that mere sentience, the ability to feel pleasure or pain, is enough to ground animal rights.

Within the world of academia, Regan was well regarded as a scholar of G. E. Moore, an early 2oth century moral philosopher, on whom he published three books.

With his wife Nancy Regan, he started the Culture & Animals Foundation. It funds intellectual and creative work on animals that “seeks to expand humankind’s understanding and appreciation of other animals, improving the ways in which they are treated in today’s society.”

In a speech on his view of the animal rights movement, he said, “We are not merely trying to change a few old habits about what people eat and wear. Billions of people will embrace animal rights only if billions of people change in a deeper, more fundamental, a more revolutionary way.”

He continued: “What I mean is nothing short of this: They must embrace and, in their lives, they must express a new understanding of what it means to be a human being.”

He is survived by his wife, his children Bryan and Karen, as well as four grandchildren.